On a chilly morning in Detroit, volunteers sort onions and load cars with groceries at a local church’s food pantry. For years, weekly food distribution events like this have been a lifeline for hundreds of Michigan families. From Detroit’s east side to rural Kent County, neighbors line up before dawn to fill their trunks with staple foods – canned goods, milk, eggs, produce – that help them make it through the week. Lately, those lifelines have been stretched even thinner than usual. Why? Because a massive federal food assistance in Michigan just got an unwelcome surprise: the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) suddenly canceled $4.3 million worth of food deliveries to Michigan’s food banks. This isn’t just a bureaucratic blip – it translates to more than 2 million meals that were expected to feed hungry families across the state, now vanished into thin air.

For Michigan families already facing food insecurity, the news felt like the rug was pulled out from under an already precarious situation. “The federal government is usually our source for feeding people, and instead they are the reason that we are not going to be able to feed people, and that's pretty sad,” said one Detroit nonprofit director, voicing a frustration echoing across pantry lines. The big question on everyone’s mind: What’s next for the parents, kids, and seniors who rely on these meals? And how are Michigan’s resilient food banks – from Gleaners in Detroit to Food Gatherers in Ann Arbor and beyond – scrambling to fill the gap?

In this article, we’ll break down the situation in a neighborly, no-nonsense way, looking at how the USDA’s cuts to an emergency food program are rippling through Michigan food bank cuts region by region. We’ll hear directly from the people running our food banks – the folks at Gleaners, Food Gatherers, Feeding America West Michigan, and others on the front lines – to understand the challenges and solutions ahead. Grab a cup of coffee (or maybe donate one to a friend who’s struggling) and let’s unpack what this all means for Metro Detroit and communities across the state.

South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

How a Federal USDA Food Program Got Cut

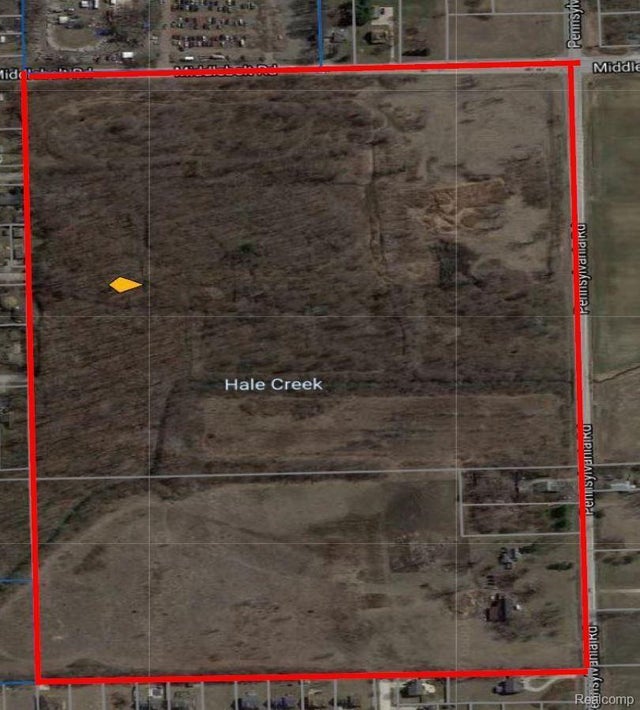

It all started with a sudden policy shuffle in Washington. In late March, the USDA quietly pulled back funding from a program called The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) – a critical source of groceries for food banks nationwide. Specifically, the USDA canceled 123 truckloads of food that were slated to arrive in Michigan between April and August, including protein-rich items like chicken, pork, and cheese. The orders – worth about $4.3 million – were part of a special USDA purchase program (using Commodity Credit Corporation funds) meant to boost food supplies during high-need times. With the stroke of a pen, those planned deliveries were gone.

Why would the USDA take food off the table, especially when demand at pantries is still sky-high post-pandemic? According to the agency, this move is about “reprioritizing” resources. A USDA spokesperson claimed that the previous administration’s emergency food purchases created “unsustainable programming and expectations,” and that the funding has been “repurposed”. In other words, they’re steering money into what they consider more stable, long-term solutions. “The COVID era is over — USDA’s approach to nutrition programs will reflect that reality,” the USDA said in a statement, emphasizing a focus on core programs and steady support. They pointed out that no changes were made to TEFAP’s base funding – the everyday pantry staples are still being bought – and that additional produce purchases from a different fund (Section 32) are on the way.

That might be cold comfort to Michigan families facing empty shelves right now. State and local officials say the cut came with no warning. Food banks had already planned on these deliveries – in some cases, even scheduled distribution events around them. “We did not see this coming. This was not on our radar…with no real time to react,” admitted Ken Estelle, CEO of Feeding America West Michigan. The sudden loss of trucks full of food has left Michigan’s network of seven regional food banks scrambling for alternatives on short notice.

Crucially, the canceled USDA shipments were high-quality, protein-rich foods – the kind of nutritious items that food banks struggle to source in large quantities. “Ground beef, pork, chicken, turkey, eggs, cheese, milk… it was really good food that we were planning on,” Estelle said. Food banks can’t just magically replace those with a snap of the fingers. As Dr. Dawn Opel of the Food Bank Council of Michigan explained, it’s a bit of a shell game now: “It’s sort of taketh away and then giveth in other ways.” Michigan might get some other USDA foods down the line, but “we still don’t know when… and we don’t know the percentage that will be allocated to Michigan”. In the meantime, the burden falls on local food banks – and their communities – to figure something out fast.

Michigan Food Banks Scramble to Fill the Gap

From Metro Detroit to the Upper Peninsula, Michigan’s food banks are nothing if not resilient. These nonprofits have battled through the Great Recession, the pandemic hunger spike, and countless local crises. They’re used to adapting when a truckload of food is delayed or when donations run thin. But a shock this big – millions of meals worth of food axed without explanation – is testing even the most seasoned teams.

Phil Knight, executive director of the Food Bank Council of Michigan (which coordinates the statewide network), put it this way: “Food banks and food bankers will come up with creative solutions to work around not having the expected meat, eggs and cheese, but…that isn’t a trade-off food banks like to make for the sake of addressing hunger in households”. In plain English: they’ll figure something out, but it might mean families get canned beans instead of chicken, or cereal instead of cheese. “People will have less access to the food that they want and need,” Knight said bluntly.

Let’s break down how this is playing out region by region. Michigan’s seven major food banks each serve different counties, but all are feeling the squeeze from this emergency food aid cut. Here’s a look at the impact – and the improvised solutions – in Southeast Michigan, West Michigan, Ann Arbor, Flint, Lansing, and beyond, straight from the folks who know these communities best.

Southeast Michigan: Metro Detroit’s Shortfall

In Metro Detroit, the Gleaners Community Food Bank is a cornerstone, supplying pantries in Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, Monroe and Livingston counties. Gleaners was set to receive a lion’s share of the now-canceled USDA food, and the numbers are daunting. All told, Gleaners is looking at a 1.4 million pound hole in its inventory for the coming months. That’s food that would have fed tens of thousands of local families. “For us to fill that on our own would cost about $850,000,” said Kristin Sokul, Gleaners’ Senior Director of Advancement Communications. To put it in human terms: if Gleaners can’t find a way to replace those 1.4 million pounds of food, roughly 25,000 families would go without meals they normally would have received this year. These aren’t just numbers – they’re our neighbors in Detroit, Downriver, and the inner-ring suburbs who rely on that safety net.

Sokul says Gleaners is determined not to let that happen. The team immediately activated a plan to fill the shortage, dipping into emergency reserves and launching fundraising to purchase replacement food. “Our team is pretty practiced in looking for resources, turning over every stone to make sure we can make the best use of what is available to us,” she explained. They’ve already allocated $250,000 from their own funds to help partner agencies (like local soup kitchens and church pantries) buy food on the open market. Still, even the best efforts can only stretch so far. “We’re starting to see that food lessen already, but in the months to come, it’s only going to get worse in those truckloads that are not going to come,” Sokul warned, referring to the missed deliveries of produce, meat, and milk that typically arrive like clockwork.

It’s not just Gleaners feeling the pinch. Forgotten Harvest, another major Southeast Michigan food rescue based in Oak Park, was also slated to receive part of the USDA shipments. Forgotten Harvest focuses on recovering surplus food from grocery stores and farms, but it too relies on federal commodities to round out the mix. Now, both organizations are coordinating closely to make sure Southeast Michigan’s network of 350+ pantries isn’t left high and dry. “At the same time we’re seeing a cut in government-donated food resources, we’re seeing hints that requests for support are increasing,” Sokul noted. With inflation and grocery prices squeezing family budgets, more people are turning to food banks just as supplies are tightening. It’s a cruel irony: need is up, and suddenly resources are down.

Local pantry leaders are doing their best to reassure families. In Detroit’s Conant Gardens neighborhood, Pastor Yvette Griffin of Pilgrim Baptist Church – which hosts a weekly food distribution – is keeping the faith. “People come here because they know that we support them,” she said, emphasizing that their doors will stay open. But she admits the recent cuts have her worried. “I’m afraid that support is going to decrease because we won’t have the tools we need to help them,” Griffin told reporters. From the front-line perspective at churches and community centers, any dip in deliveries means making agonizing choices – do you give each family a little less food, or turn some families away? Nobody wants to do either.

The consensus in Metro Detroit is that this is a “do whatever it takes” moment. Gleaners and Forgotten Harvest are rallying donors and volunteers, and even exploring whether local farms or companies can donate extra to get through the crunch. Still, as Sokul candidly put it, “the unfortunate reality is there could be an impact across what we’re able to provide in variety or volume.” In other words, families visiting pantries might notice the milk or meat runs out faster, or the bags of groceries are a bit smaller for a while. It’s a scenario Southeast Michigan’s food banks are fighting hard to prevent – nobody wants to tell a grandmother in line that there’s no chicken this week – but the next few months will be a true test.

.png) South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

Ann Arbor & Washtenaw County: Food Gatherers’ 15% Gap

Over in Washtenaw County, the team at Food Gatherers – the food bank serving the Ann Arbor area – is also reeling from the news. The USDA cut is hitting their operation particularly hard. “It comprises 15% of our total food distribution last year, or more than the equivalent of 1.2 million meals,” said Eileen Spring, President and CEO of Food Gatherers. Think about that: nearly one out of every six meals Food Gatherers provided in the past year came from the now-canceled federal shipments. Losing that chunk in one fell swoop is, as Spring put it, “hard to replace so quickly.”

And it’s not as if Food Gatherers had a bunch of excess slack – far from it. Like many food banks, we have been distributing more food than we ever have before, serving more neighbors, Spring noted, because demand at food pantries has been high since the pandemic. In Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti and the surrounding communities, Food Gatherers and its partner pantries are still seeing elevated need. Working families, students, and seniors on fixed incomes are struggling with the high cost of living (any local can tell you grocery and gas prices haven’t exactly dropped). So this cut comes at the worst possible time – just as Washtenaw County’s hunger relief network has been running full tilt, trying to keep up with need.

Food Gatherers is now hustling to find alternative food sources for the spring and summer. They’ve reached out to other regional suppliers and are prepared to spend more of their budget on purchased food if needed. The organization has a strong local donor base (Ann Arbor folks have big hearts), and Spring is hopeful the community will step up as it has in past crises. Still, finding an extra 1.2 million meals is not a small ask. They can perhaps source more produce from local farms or excess dairy from Michigan’s agricultural sector, but replacing the lost protein (meats and eggs) will be especially challenging. Those items are expensive and were supposed to be provided free by the USDA.

One silver lining: Food Gatherers’ efficient distribution network and partnerships might help stretch whatever food they do have. Washtenaw County has a robust coalition of charities, and they’re coordinating to make sure no family falls through the cracks. For example, if a smaller church pantry in Chelsea runs low on staples, Food Gatherers can redirect supplies from its Ann Arbor warehouse to cover the gap. Communication is key; Spring and her staff are in close contact with other Michigan food banks too, sharing ideas on how to cope.

The worry, though, is palpable. The longer-term question is whether the USDA will resume these kinds of bonus food shipments or if Food Gatherers must permanently adjust to a new normal of reduced federal support. For now, Spring’s message to the community is one of determination: they will not let Washtenaw County go hungry. It might take creative solutions – more food drives, tapping into Michigan’s farm surplus when possible, or offering slightly different items – but families will still find help when they knock on Food Gatherers’ door. “We’ve got more people to feed than ever, and we’re going to find a way,” one Food Gatherers volunteer told me with resolve. That neighborly spirit is Ann Arbor at its best.

.png) South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

West Michigan: 32 Truckloads Canceled in Kentwood

In West Michigan, the cut has been just as severe, even if the community profile is a bit different. Feeding America West Michigan, based in Kentwood (just outside Grand Rapids), was expecting 32 semi-truck loads of USDA food to arrive between April and July. All 32 trucks were canceled. “The 32 truckloads equate to around 600,000 pounds of food,” said CEO Ken Estelle – roughly a full week’s worth of supply for his organization. To put that in perspective, Feeding America West Michigan distributes about 23 million meals worth of food a year, through a network of 800 partner agencies across 40 counties (stretching from the Grand Rapids metro area up to the Upper Peninsula). Losing those trucks means roughly 400,000 meals that would have fed families from Muskegon to Marquette aren’t coming.

Estelle was stunned by the news. “We did not see this coming… a 600,000-pound dip in supply with no real time to react,” he said, echoing the disbelief felt by many of his peers. Those canceled deliveries included high-demand foods like protein and dairy, which food banks can’t easily replace with local donations. West Michigan’s community is generous, but no food drive is going to suddenly produce 300 tons of meat and cheese. The timing also overlaps with the end of the school year – a period when food banks typically gear up to help families whose kids lose access to school meals in the summer.

So what is Feeding America West Michigan doing? First, they’re tapping every reserve and relationship they can. Estelle said they’ve identified about $180,000 in their budget that they can reallocate to purchase food – a decent chunk, but still only about one-sixth of the ~$1.1 million worth of food they lost. They are in talks with other large charities and even some retailers to see if bulk food can be acquired at a discount. West Michigan’s agricultural community might assist too; for instance, if a local poultry processor has an oversupply, the food bank could take those chickens off their hands (an approach used in past shortages).

Even with those efforts, Estelle is bracing for some changes on the front lines. “It won’t impact the volume [of food distributed],” he reassured – they are determined to keep serving everyone who comes for help – “but instead of it being protein, it will likely be more produce.” In short, nobody will be turned away, but the mix of foods in the pantry boxes might lean more toward vegetables and starches if meat isn’t available. This is a significant shift; while any food is better than no food, it means families may have to adjust meal plans. It’s also tough on those with limited cooking facilities – for example, a family living in a motel might find raw potatoes and squash less immediately useful than canned stew or frozen chicken. West Michigan’s food bank is aware of these issues and will try to provide whatever protein they can from alternate sources, but some compromises are likely.

Ken Estelle also highlighted an often overlooked ripple effect: local farmers are hurt by these cancellations, too. “The food that the USDA ultimately processes and provides to us comes from farms,” he explained. “Michigan is the second largest provider to the USDA of commodities behind California, so anytime the USDA cancels orders or trucks, ultimately somewhere a farm is being impacted.” In this case, produce and dairy that would have been bought from Michigan growers for the federal program might now rot in fields or go unsold. It’s a lose-lose: farmers miss out on income, and families miss out on food. This point underscores why so many in Michigan (including elected officials) are unhappy with the USDA’s abrupt move. It disrupts the whole food chain.

Despite these challenges, West Michigan’s spirit is strong. “We will absolutely have food available to every one of our distributions and food pantries,” Estelle promised, “It may not be the same food we were anticipating, but we will definitely have food for folks that need help.” In Grand Rapids, Feeding America West Michigan’s warehouse crews are busy re-working logistics, ensuring that every scheduled mobile food pantry and every partner agency still gets deliveries – even if they have to short some items or substitute others. The organization has weathered crises before (like when the pandemic initially disrupted supply chains in 2020), and they’re applying those lessons now. They are leveraging relationships with food banks in other states too; if an Iowa food bank has extra shelf-stable items, for example, sometimes they can arrange a swap. Such collaborations might help patch the holes in inventory.

West Michigan’s many small-town pantries – from lakeshore communities like Muskegon to northern outposts in the U.P. – are keeping a close eye on the situation. The message to families has been consistent: please still come to get help. There may be a bit less milk or meat in the boxes, but there will be boxes. As one Grand Rapids pantry manager said at a recent distribution, “We might have to give you beans instead of peanut butter, but we’re not going to let you go hungry.” That determination, shared by volunteers and staff alike, is what will carry West Michigan through this storm.

Flint & Eastern Michigan: Thousands of Meals at Risk

In the Flint area and across eastern Michigan, the impact of the USDA cut is also significant, though in sheer numbers a bit less than in Southeast and West Michigan. The Food Bank of Eastern Michigan (FBEM), based in Flint, serves 22 counties ranging from the Thumb area (think places like Saginaw, the Thumb, and Flint) up to the northeastern lower peninsula. FBEM was set to receive a portion of those federal food shipments, and their leaders estimate about 399,000 meals worth of food is now lost for their region. That’s nearly 400,000 meals that would have gone to families in cities like Flint, Saginaw, and Bay City, as well as many rural communities in between.

For Flint in particular, where the poverty rate is high and the aftermath of the water crisis still strains household finances, losing any food aid is tough. FBEM works with roughly 700 food distribution sites (pantries, soup kitchens, shelters) across its territory, and demand at those sites has been climbing. Much like elsewhere in Michigan, Eastern Michigan’s food bank has been distributing record amounts of food in recent years – in some months 50% more than pre-pandemic levels, as one FBEM report noted. The USDA commodities were a vital supplement to their efforts, especially for providing protein and dairy to balance out the non-perishables they collect through donations.

While we don’t have a direct quote from FBEM’s CEO in this report, it’s clear from their public statements that they’re concerned but proactive. The Flint-based food bank immediately began advocating for state assistance to help plug the gap. They’ve alerted community partners and are examining their inventory to prioritize the most nutritious items for distribution. Fortunately, Eastern Michigan had some advance notice (a week or two) to prepare once word of the cancellations came down. They’ve been re-routing some of their Michigan Harvest Gathering donations (an annual food drive) to cover needs that the USDA food would have met.

One of the biggest challenges for Eastern Michigan is geography – serving 22 counties means long drives and lots of smaller towns that depend on periodic mobile pantries. If there’s less food to put on each truck, some remote areas might get fewer visits or smaller rations. FBEM is trying to avoid cutting service to any county; instead, they might reduce quantity slightly across the board so that every community still gets something. In Flint itself, larger pantries are bracing for possibly longer lines, as families who might have gotten by with the help of a once-monthly federal commodity distribution now turn to local charities for extra help.

The Food Bank of Eastern Michigan has a track record of resilience – during the Flint water crisis, they orchestrated massive water and food distributions under emergency conditions. Compared to that, this is a more subtle crisis, but it affects a broad swath of their day-to-day work. We can expect FBEM to lean on its collaborations with churches, the United Way, and local businesses. Already, there’s talk in Flint of organizing a special community food drive to collect protein items (canned tuna, peanut butter, etc.) to make up for the missing USDA protein packs. If any community knows how to rally in tough times, it’s Flint – they’ve been through the wringer and come out the other side determined to help each other.

.png) South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

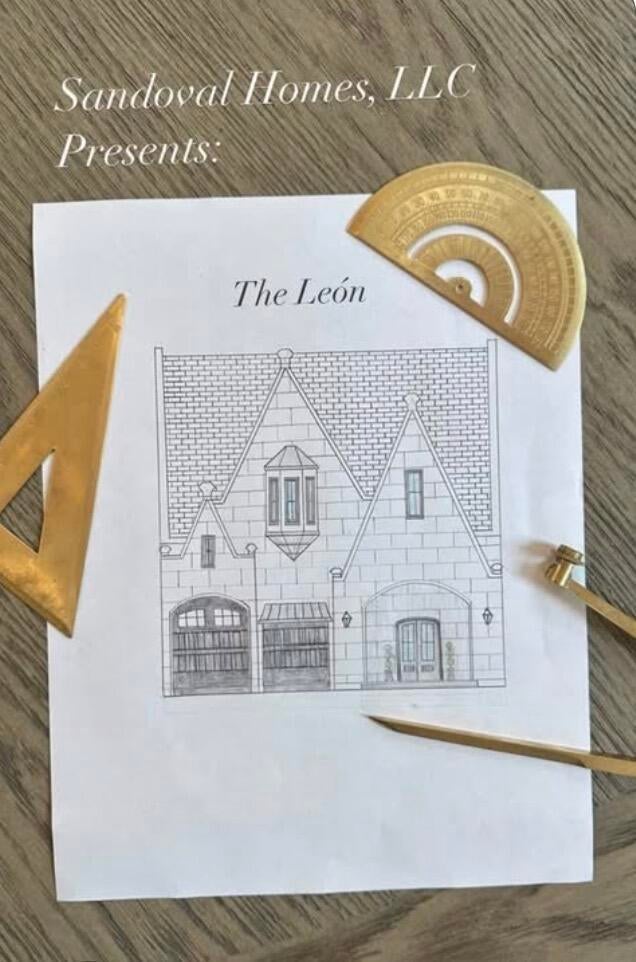

Lansing & Battle Creek: Mid-Michigan Feels the Squeeze

In mid-Michigan, including the Lansing area and down through Battle Creek/Kalamazoo, food bank leaders are cautiously optimistic that they can manage the immediate shortfall – as long as things don’t get any worse. The Greater Lansing Food Bank (GLFB), headquartered in Bath Township just outside Lansing, was set to lose roughly 150,000 meals due to the USDA’s cancellations. The GLFB serves seven counties in the Lansing region, and while 150,000 meals is nothing to sneeze at, it represents a somewhat smaller slice of their total distribution (Lansing’s population is smaller than Detroit or Grand Rapids). GLFB’s CEO, Michelle Lantz, has indicated that through careful planning – and perhaps drawing on some surplus inventory from earlier in the year – they hope to absorb that hit with minimal impact on families. They’ve been expanding their Garden Project (which helps locals grow their own food in community gardens) and other creative programs to boost food access, which might provide a little extra fresh produce to offset the loss of USDA items.

Further southwest, the South Michigan Food Bank in Battle Creek (serving 8 counties including Calhoun, Kalamazoo, and Jackson) is seeing a similar shortfall. CEO Peter Vogel reported that they will receive about 400,000 fewer pounds of food this year due to the federal cut – roughly a 3–4% reduction in their annual food supply. In meal terms, that’s on the order of 150,000 meals not coming to South Michigan communities that were expected. The good news, if you can call it that, is that 3–4% is a relatively small portion of their total distribution; Vogel’s team believes they can make up most of it through other sources in the short term. “There may be a way to offset the difference in 3 or 4%,” Vogel said, noting that tighter budgeting and a bit of luck with donations might cover this initial gap.

However, Vogel is keeping a close watch on the horizon. “If it becomes substantially bigger cuts than that, or substantially more people coming and needing food in my area, we’re going to be really limited in our ability to do that,” he warned. In other words, the cushion only goes so far. If additional federal programs are trimmed (and there are indeed rumors of further USDA adjustments, as well as concerns about possible SNAP (food stamp) reductions in the future), then the South Michigan Food Bank could quickly find itself underwater. Vogel mentioned that talks of SNAP cuts and other economic strains are troubling because they could drive even more people to seek pantry assistance, just as resources plateau or shrink.

For now, places like the Battle Creek food bank are doubling down on fundraising and efficiency. Vogel has launched efforts to increase local fundraising to buy food, and they’re making sure every donated dollar is stretched. Both GLFB and South Michigan Food Bank have been investing in infrastructure (like better warehouse storage and logistics software) which helps them do more with less waste. Those investments will be tested now. They’ve also built up a bit of inventory of shelf-stable foods which can be tapped for a few months if needed.

Community support in mid-Michigan tends to rally through events – for instance, Lansing’s WLNS TV is partnering with GLFB for a food drive, and in Kalamazoo/Battle Creek, some companies are stepping up with matching donation campaigns after hearing about the USDA cuts. These local efforts can buffer the impact, even if they can’t entirely replace what was lost.

Importantly, no one is panicking – instead, food bank leaders are planning cautiously and appealing to the community’s sense of solidarity. “Southwest Michiganders” shouldn’t go hungry because of a policy change, Vogel implied, and he’s hopeful neighbors will look out for one another. The coming summer will put that hope to the test. Mid-Michigan families, especially when kids are out of school, often rely on food banks to get through each month. If the food isn’t there, we could see more people traveling farther to find help (for example, driving from a small town to Lansing or Kalamazoo). Food banks are coordinating so that if one pantry runs out, they can direct clients to another nearby. It’s a patchwork safety net, but everyone is committed to catch as many in need as possible.

.png) South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

South Michigan Food Bank, Facebook

What’s Next for Families Facing Food Insecurity?

With all the adjustments and emergency measures, you might be wondering: will families notice the difference? Unfortunately, some likely will. The loss of 2+ million meals worth of food means that food-insecure households may receive less food, or less variety of food, from their local pantries in the coming months. Instead of a couple boxes of groceries, maybe it’s one box. Instead of fresh meat and eggs, maybe more canned goods and beans. For a family struggling to put dinner on the table, these nuances matter – it can mean the difference between a balanced meal and a meal that fills the belly but falls short nutritionally.

Michigan’s food bank leaders are doing everything in their power to minimize the pain. They’re leveraging community donations, finding creative substitutions, and advocating at the state and federal level for support. In fact, the outcry over this USDA cut has already reached Lansing and D.C. – lawmakers are pressing the USDA to explain itself and to find ways to restore the aid. There’s hope that some funding might be reinstated or that future programs (like the mentioned Section 32 produce purchases) will send additional food to Michigan later in the year. However, any such relief likely won’t kick in for months. As Phil Knight noted, the food bank network is staring down a potential “six month food gap” that they have to bridge on their own.

For the families facing food insecurity right now, the advice from community organizations remains: keep seeking help when you need it. Michigan’s network of food banks and pantries is still strong and functioning. If you’re in Metro Detroit, Gleaners and Forgotten Harvest continue to run distribution sites and pantry partners – there may be a little less in stock, but you will not be turned away. In Grand Rapids and the West, Feeding America West Michigan’s mobile food trucks are still rolling into parking lots from Kentwood to the U.P. on schedule (just maybe with more carrots and fewer chicken breasts than before). In Ann Arbor, Flint, Lansing, Battle Creek and beyond, the compassionate folks behind Food Gatherers, FBEM, GLFB and South Michigan Food Bank are adjusting but still very much open for service.

One thing this saga has highlighted is the incredible resilience and solidarity in Michigan’s communities. Time and again, when faced with hardship, Michiganders pull together. As an example, right after the cuts were announced, a local coalition in Detroit began organizing extra food drives to support Gleaners. In Grand Rapids, a group of churches quickly raised funds to buy a load of canned protein to distribute. These grassroots responses can’t entirely replace federal support, but they embody the neighborly spirit that Metro Detroit moms, dads, and savvy locals alike take pride in. We look out for each other here.

The coming months will undoubtedly be challenging. Food bank staff will be working long hours to source and distribute whatever they can get. Families might have to visit an extra pantry or stretch the food they do receive a bit further. But there is also reason for optimism. By late summer or fall, the USDA’s “reprioritized” funding may translate into new shipments (albeit maybe more fruits and vegetables) reaching Michigan. And awareness of hunger issues is growing – more community members and businesses are learning about these cuts and asking how they can help. That awareness can spur donations and volunteerism, which are the backbone of food security efforts.

As we navigate this period, it’s worth remembering a powerful perspective shared by Phil Knight of the Food Bank Council: “Let’s stop thinking about people who are struggling with hunger as a problem to be solved,” Knight said. “Instead, let’s start thinking of them as people who are worthy of an investment.” Families facing food insecurity are our neighbors, coworkers, and friends – and investing in making sure they have enough to eat is an investment in our community’s health and future.

Michigan’s food banks are on the case, and they won’t stop fighting for that investment. As a community, we can continue to rally around those in need, ensuring that even when budgets are slashed and truckloads canceled, no family has to wonder if tomorrow’s dinner will actually be there. In the end, that’s what being a community is all about – weathering the tough times together and holding each other up.

The situation with the USDA food program cuts is evolving, and Michigan’s response will too. For now, the best we can do as informed neighbors is stay aware, support our local food banks if we’re able, and above all, extend understanding and compassion to those among us who are facing hunger. The road ahead may be challenging, but with the smart, resilient, and caring people in our Michigan communities, you can bet we’ll find a way to get through this – together.

DON'T KEEP US A SECRET - SHARE WITH A FRIEND OR ON SOCIAL MEDIA!

.62.png)

Leave A Comment